Historical revisionism and fake news

History is always the most revered authority, and the ultimate teacher. It is empirical proof of expected results from conditions and contexts as naturally presented by science or as conjured and executed by minds. What has happened, has happened, and there is always a lesson learned.

But the life that History gives to concepts and principles can be limited not only by the durability of physical archives but the fickleness of minds — who may carelessly forget lessons learned, or, worse, actively tamper with facts and data to suit biases and whitewash personal culpability in the deconstruction and revision of what may be a notorious Past.

An example of negative historical revisionism is David Irving’s controversial book, Hitler’s War (1977), where the dictator Adolf Hitler is shown as innocent of the Holocaust and that only Heinrich Himmler and his cohorts masterminded and executed the genocide of six million Jews in Nazi Germany between 1941 and 1945.

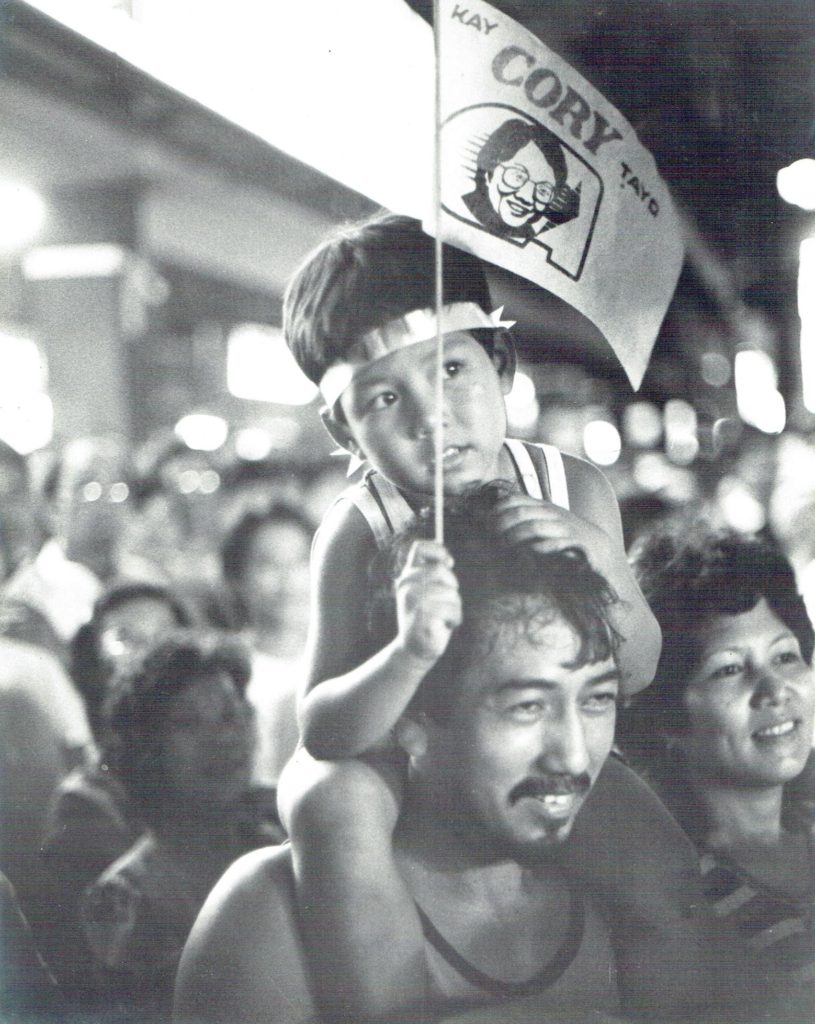

Are Filipinos about to accede to a revision of history over the 14 year-dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos — editing out as well the glorious EDSA People Power Revolution that ended the most notorious period that killed about 3,240, imprisoned 70,000, and tortured 34,000 people from 1972 to 1981, according to data of Amnesty International?

On the 48th anniversary of Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law, an online conference on historical revisionism titled “Balik Ka/Saysay” was held from Sept. 21-25 by the Ateneo University-based Asian Center for Journalism (ACFJ) and Consortium on Democracy and Disinformation, in partnership with Tanggol Kasaysayan and Bulatlat. The conference focused on disinformation and the machinations of politics, on the inadequacy of education, and extensively described the exacerbating influence of social media and fake news on perception and the formation of new mores and values.

Keynote speaker at the ACFJ webinar was novelist Lualhati Bautista (Dekada ’70 and Gapo) who went underground during the Marcos martial law, and despite the strict censorship imposed by the government, wrote about the anxieties and fears of ordinary Filipinos in those tremulous times. “Never forget; never again!” was her heart-wrenching message. But for those listening to her recounting of the hounding and torture of those who defied Marcos then, her horrible reminiscences might have fallen differently on unreceptive ears of those who did not directly experience martial law. How devastating to hear a young reactor at the conference, a self-proclaimed “fan” of Ms. Bautista for her art, dismissing the pathos of a dark history by concluding a long-winded to-and-fro on doubting what may be “exaggerations” in the telling of the martial law situation then. “It is not my context,” she might have said in so many words, as she quite directly insinuated to this aghast listener who has seen Lualhati Bautista’s horrible scenarios in the context of 48 years ago.

“It is not my context” is the obvious indifference of most of the younger generation that did not see the excesses and horrors of martial law played out in reality. Adding cold emotion to whatever near-boiling empathy might be brought by stories told by seniors is the obtrusive social media virtual reality replete with ready fake news that the younger generations might have made its instant real Reality — their “context.”

At the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) theater showing early in the year of Kingmaker, a documentary by Emmy-winning filmmaker Lauren Greenfield about former First Lady Imelda Marcos, an open forum was held mainly to wrap up for attending groups of students from various schools, the “Never Again” information campaign of rights groups to educate the younger generation about the perils of autocratic government. Resource person Etta Rosales, tortured and imprisoned in Martial Law, gave inputs and answered questions from the students. It was the same basic concern of the Youth: “What is in it for Me?”

Recalling that open forum, and reviewing the ACPJ conference on historical revisionism, it sends chills through this older person to realize that a better way must be found to protect those who have not personally experienced Martial Law and its excesses from the frightful chimera of History repeating itself. The protective instinct of the Elders must work within the context of the Youth, in their Reality and in their Present — and perhaps resignedly acquiesce to their focus on “What is in it for Me.”

University of the Philippines Professor Francisco A. Guiang in a comment about historical revisionism cites the historian Carl L. Becker who said that “Every generation writes its own history… we build our conceptions of history partly out of our present needs and purposes…” (1955). Hence, while the older generations might be concerned about the immoral revision of their history, the younger generations are focused on writing their own, based on their present needs and purposes, their values and principles, taught to them by their parents by example, or by individual collective experiences and environments.

It must be admitted that in the 14 years of the Martial Law experience, victims and beneficiaries all have been writing history by the acceptance, refusal or compromises made then, and many have effectively rewritten and revised that history in the 34 years after the euphoric EDSA People Power Revolution, directed by changing individual and collective present needs and purposes. Some guilt might lie in admitting that the older generations might not have shown good example and firm guidance to the younger generations as to the values and principles that urged the collective judgment then that martial law the way Marcos did it was wrong and unconscionable.

Why did the Filipino people allow President Rodrigo Duterte to bury the dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the Libingan ng Mga Bayani? We have revised History. Marcos is now a hero.

The Marcoses plundered the country’s coffers, with various estimates putting the amount at between $5 billion to $10 billion, as reported by ABS-CBN in 2017. The Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG), the body going after the Marcoses’ ill-gotten wealth, is still recovering this money; over the past 30 years, at least P170 billion have been recovered. The Supreme Court dismissed in 2018 a civil suit seeking the recovery of over P50 billion in moral damages and P1 billion in exemplary damages sought by the PCGG over the Marcoses. The Sandiganbayan in 2011 junked the case, saying the PCGG failed to prove that the defendants connived to amass ill-gotten wealth.

In 2008, former First Lady Imelda Marcos was acquitted of an $863-M corruption case involving 32 counts of illegally transferring wealth to Swiss banks abroad during her husband’s 20-year rule. Would you wonder why the documentary Kingmaker did not jar the young viewers at that open forum held after the screening, despite the first-person account of Etta Rosales of her torture during Martial Law? Imelda is guiltless. History has been re-written.

It seems that the onus of responsibility to keep the integrity of history clearly rests on those survivors of Marcos’ Martial Law. Alas, so few of the older generation still have the passion to pursue the noble upholding of the Truth. At least those who still care that History must not repeat itself for the younger generations must devise and design active ways, albeit from physically deteriorated capabilities (but still-solid minds) to inculcate values and principles above present needs and wants of the younger generations.

The best way can only be to always visibly and audibly, strongly oppose corrupt and immoral practices in present-day government and society in general that, in the wisdom of age and experience, can be a useful template for the younger generations. The older generations are still writing their history, and their legacy.

Amelia H. C. Ylagan is a Doctor of Business Administration from the University of the Philippines.